On Eva Hesse and Gall

When at sixteen and a half, the aspiring painter Eva Hesse, walked into the squeaky teen dream Seventeen magazine and asked for a job, she put it down to sheer “gall”; this heady mix of aspiring girlhood and gall encapsulates Hesse’s early ambitions, bolstered by a certain level of beauty and privilege, but also hardship. Gall’s etymological root is in bile; it refers to something bitter, or else bold and impudent behaviour that does not show due respect for authority. Gall is, I think, what we need to live in the present moment.

Over the winter and while the earth has been dormant, or resting, I have had the privilege of trying to write another book and reconcile with writing anything when further afield the world is burning. By working with and on the land, seasonally, I carve out a brink in time to write—like really write—every day kind of writing but I am, like everyone else, wondering what it’s for. A book is, at best, a process of interrogation—turning the tables on knowledge systems, beauty, power. I find reprieve in Eva Hesse—to whom much of the final chapter is dedicated and who has got me thinking about gall.

Hesse, who was born in 1936, was on the one hand bold and impudent, and on the other tentative—haunted by the many personal losses that shaped her, not least her extended family to the holocaust and later, her mother to suicide. “Why is it that I cannot see objectively what I am about?”, she wrote in her diary. “My vision of myself and of my work is unclear, clouded. It is covered with many layers of misty images… I do want to simplify my turmoil.’’

What Hesse didn’t know but would soon discover is that turmoil is not clear or simple, but complex and lasting; and that within her clouded work and layers of misty images lies the power of obfuscation, which is perhaps what she also wanted for minimalism—to disrupt it as a kind of doctrine.

The last five years of Hesse’s short life were characterised by the grid, but rather than something to comply with, it became a parameter to breach. Hesse was a brilliant draftswoman long before she reached sculpture and her exploration of the grid began with a series of graphite pencil drawings that from a distance look like deeply uniform systems abiding to the parameters of the graph paper—the of stuff of engineering or architectural design. To understand Hesse we must get closer: squeezed into each square was a circle that corrupted the paper’s ‘proper’ use. Hesse made this series in 1966, but there is evidence of the grid from during her time in Germany.

In June 1964, Hesse and her husband the artist Tom Doyle went to Germany because Doyle had been commissioned to create some of his stone works for the German industrialist and collector Arnhard Scheidt, who Lippard writes, ‘decided it would be easier to transport the Doyles than the work. He offered them a year to work in his abandoned factory buildings in Kettwig-am-Ruhr with support and materials, in exchange for a certain amount of sculpture.’ Hesse was apprehensive about returning to Germany, which had never been her heart or father-land (she was born a few years after her parents left the country in 1933), and it threw up “terrible gruesome nightmares’’, which gradually lessened and turned into ‘‘day dreaming, phantasizing.”

The couple lived in a recently defunct textile factory; at first, Hesse was tormented by memories—those inherited and felt—but she found reprieve in three dimensional form, salvaging what had been left behind or brought to her by the workers as they dismantled the building around them. It was here that she traded the flat surface for sculptural form, pushing knotted plaster-soaked and dripping string tubes through a mesh screen. Although the work was either lost or destroyed, it set a precedence for future works in which she would fabricate the grid in low stakes materials, and by hand, rupturing the hard lines of minimalism through the contingencies of her own body; a tick, a tensed muscle, a distant distraction. This year and the brief years that followed, would be remembered as Hesse’s breakthrough years, but permutations of her systems and structures, and sculpture, are also present in a series of vibrant mixed media collages from 1963 and 1964, in which strange forms—anatomical parts like lips and heavily lashed eyes, and mechanical-looking parts like screwdrivers or wire—are rendered in gouache, watercolour, ink and graphite on paper. Hesse wrote to her friend Sol LeWitt that “they had wild space, but constant, fluctuating and variety of forms, etc.” Some have suggested the collages are figurative, others that they are precursory or preparatory notes for Hesse’s sculpture. There are traces of the grid in the strange leggy boxes in Untitled, (1963)—akin to those transgressive squares on the graph paper; they supersede and precede what came next.

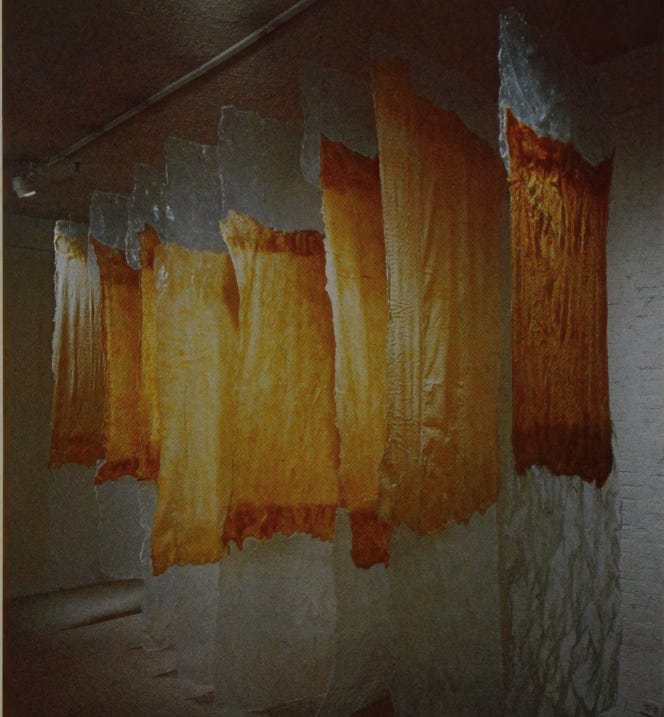

In 1968, Hesse began Contingent—a series of hangings that were made from cheesecloth coated in fibreglass and latex. Lined up and suspended from the ceiling, their luminescent orange pigment gives way to the sheer translucency of the base materials, at the edges, extending the grid into sculpture.

Not long after the Doyles returned to New York, they split and Hesse embarked on a highly productive period of work. In 1969, Hesse was diagnosed with a brain tumour and despite having surgery, died in 1970. She was 34.

In those final days, making small models and drawings from her hospital bed, she wrote that “the lack of energy I have is contrasted by a psychic energy of rebirth. A will to start to live again, work again, be seen, to love …"